By Eric Seals

By Eric SealsStaff Photographer

Detroit Free Press

Shooting and producing video at the Detroit Free Press has often involved searching for features or slice-of-life stories that let me be creative and have fun telling a story, while constantly challenging myself. Sometimes, however, I like to produce stories that have a newsier edge to them, in order to mix things up and push me out of my comfort zone.

Working on this piece, "The Search for Missing People in Detroit," was another opportunity for me to try that. Here's what went into planning, shooting and editing this video.

Our police reporter, Gina Damron, had started working on a story about a new Missing Persons Unit inside the Detroit Police Department. The assignment was given to me to spend a couple of days on it, turning it into a 1:30 video piece for Web and the local CBS affiliate and stills for the newspaper. After spending the first day with the officers, based on the access I was given, the comfort level we had with each other and seeing the potential of a good story developing, I wanted to pursue it harder and work it into a longer piece.

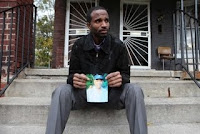

Before I got involved, Gina had already made contacts and talked with a few victims of people missing in the city. She told me the story about Sandrew King (pictured) and how when he talked about his missing grandfather, he was riveting. The way he told his story took you into the void inside him and the lack of closure he still feels.

This is one of the benefits of working with a good reporter who also understands the power of good visual storytelling, what’s involved in the process and what it takes to pull it all together.

I sat Sandrew down in front of a plain, non-distracting background, lit him with an octagon softbox (with four 85 watt CFL lights) and we both interviewed him. We asked questions that got him to get into his feelings about the night his grandfather disappeared, the loneliness and lack of closure he and the family felt the past year. We got him to recount his search for him in abandoned homes in Detroit, as he wondered if he was still alive.

Sandrew was that type of interview for me that is usually hard to get, where a person is just so expressive, with emotion in the voice and dramatic pauses (and not the kind where you know someone is going overboard, playing to the camera). He was just real genuine in talking with us to the point where he just forgot about the softbox and all my gear around him. He was on a mission to let others know the emptiness that is still inside him. “I wouldn’t wish this kind of feeling on my worst enemy,” he said towards the end of our time with him.

The emptiness and emotion in this piece was powerful to convey and a critical element in holding the viewer glued throughout the 4:37 piece. A book I’ve read three times and recommend, talks about emotions as being an important element that can make us all better storytellers. It's called “In The Blink of An Eye” by legendary film editor Walter Murch.

Murch asks, “How do you want the to audience to feel? If they are feeling what you want them to feel all the way through the film, you’ve done about as much as you can ever do. What they finally remember is not the editing, not the camerawork, not even the story -- it’s how they felt.” He says in film editing, and I’d say in shooting as well, that emotion, story and rhythm come before anything else in the frame or the timeline.

Throughout the shooting process and before sitting down to edit in Final Cut, I was constantly thinking, asking myself what I had and what direction I was steering this piece in, and formulating its structure. Did I have enough b-roll? Did I have anything to cover when Sandrew talks about the emptiness he feels? Did I need to do more active interviewing with the police?

I’ve learned from others that the collaborative process between videojournalists and the print reporters we work with is very important and special. There’s no doubt that as visual storytellers, we have a big stake in the final outcome and the look or style of the piece. Working with Gina and other reporters at the Free Press it is always about STORY -- not my story or her story, but the viewers’ story. No matter how short or long a piece is, if we are not in tune together with structure and bouncing ideas off each other for both the written and visual piece, the work will fall apart or not be anywhere near as good as it could be.

The idea for narration didn’t enter my mind until I was halfway done shooting. There are many opinions out there about narrating. Many people don’t care for it, claiming, “I don’t want to sound like those TV guys.” Others prefer using text. For me narration can work well, especially in a complicated piece. Narration really helps tie or bridge things together, it shortens the overall length of the piece and with good (but short) script writing and enunciation, it can really help get the viewer to understand the story quicker. Good examples can be found everywhere, just look at some of the really nice work produced by Frontline, NOVA, ESPN, and HBO documentaries.

I’ve been doing video storytelling for two-and-a-half years at the Free Press. Often in the past after shooting a piece, I’d sit in front of a 30-inch monitor staring at a Final Cut timeline that just as well could have been a big table with lots of jigsaw puzzle pieces all over it. I’d usually say something like, “OK, now what the hell do I do?” I’d have no good sense of story, or structure or what I'd want to say. It was as if I was just out gathering stuff: just making pretty visuals and getting good crisp audio.

In the past year I feel like I’m just starting to understand the story structure and what I want to say before the edit. For others this might be a no-brainer, but for me there are so many balls I juggle all the time -- from a constantly changing story, the technical issues, the visuals, the learning curve -- that add up to a big commitment of time and energy. When the story arc starts to unfold in front of you, it’s a lot more gratifying than sitting in a dark video editing room waiting on an epiphany that we all know very rarely shows up.

As with many things we do in this business, we are never completely happy with the finished product. There are aspects of this video I’d love to change in hindsight, from incorporating less video at the beginning of Sandrew holding his grandfather's picture to perhaps ending it with the camera looking up at the bare trees. Those ideas and others came from seeking out opinions on my edit, keeping an open mind, and seeking and learning from constructive criticism. I’m always looking for tips from colleagues at the Free Press and others whose storytelling I respect at newspapers and TV stations across the country.

So let me ask you -- did the "Missing People" video hold your interest the whole way through? Did it leave you wanting to know more than I told you in the 4:37 piece? How do we balance the short time element of video storytelling on the Web with trying to answer questions that will be raised by the viewer? How can we stay committed to good storytelling without letting the piece drag on and on?

Do emotions (happy or sad and reflective) play an important role in the stories you tell or in the videos you watch? Just like shooting for Cartier-Bresson's decisive moment in a still image, we need people to feel something when they watch what we do. But should emotion supercede the story or the rhythm of the piece?" Let us know your thoughts.

Look for more of Eric Seals' videojournalism on KobreGuide's Detroit Free Press channel.

No comments:

Post a Comment